It’s been a hot minute since the last time I wrote here—between then and now there have been thousands of miles of air travel, a lot of faffing about on Instagram Stories, even more unprofessional faffing about on Twitter, a whole new language learned(-ish), many performances with and without other people, a move to a new city, a wild midterm election, a truly terrible season of House of Cards, several excellent high-grossing movies, some awful movies that made a lot of money anyway, some excellent movies that didn’t make enough money, the discovery of an awesome TV show, and the slow realization that although I haven’t had enough time for all the sleep I should have gotten this year I somehow had the time to watch a lot of movies and TV.

Hmm.

When I wrote last year’s post about branching out of standard piano repertoire (recap: it’s all by white dudes) to explore music by women and people of color, I’ll admit I had a secret little fear that I wouldn’t be able to follow through and that my good intentions would wilt and I’d go back to my usual diet of Bach, Beethoven, and Chopin.

Well, I’ve been chugging along at my personal crusade of searching out and learning music by female composers, and I’m happy to report that 1) I haven’t given up, and 2) I have a lot to say about the journey so far, which has been a roller coaster of fear and discovery (hence the blog title). There are a lot of unique challenges that come with straying from the canon, as well as a lot of really special bonuses that you don’t get playing music from the standard menu.

This post will be a two-parter, because I started writing this and it got…really long. So Part 1 will focus on the challenges I’ve encountered so far, and Part 2 will be all about the wonderful, magical parts of the process that (spoiler alert!) make the challenges worth it.

So let’s get into this, shall we?

The Challenges (So Far)

Note the first: Although I’m specifically writing about the challenges of learning music by women, these problems apply to anyone learning music by any non-canonic composer. I’m using “non-standard” or “non-canonic” to mean any composers who are not typically covered in course curriculums, or whose music is not typically represented in the standard repertoire assigned to classical pianists, both at pre-college and conservatory/university levels. These issues do apply to some male composers, but they disproportionately affect the majority of female composers.

Note the second: as examples I’ve linked or shown searches/products on Sheet Music Plus only; I’ve done this because SMP is the easiest point of comparison for the reader, with search results that I can reliably permalink or screenshot, and its catalog is representative of the catalogs of other sheet music retailers. However, SMP is not the only company from which I purchase sheet music, and my criticisms are not directed at them, but at editors and publishing companies as a whole. Disclaimer: the SMP links are affiliate links.

1. There are limited options for edited, published music by women.

There are so many great composers who happen to be female, but getting my little consumer hands on their music has been! so! difficult! Finding and ordering sheet music is its own exquisite little hell that could be its own blog post, but I’ll go into the problems specific to non-standard composers.

I’m not new to limited selections; for example, when you buy music by a 20th or 21st century composer, there’s typically only one edition you can possibly get, because that publisher holds the sole rights to that music. But I’ve been looking for music by composers like Clara Schumann, Cecile Chaminade, and Louise Farrenc—women who have been deceased long enough that their music is in the public domain, and whose music anyone can edit and publish and sell.

Yet while I have dozens of publishers and editors to choose from when I want to learn a Beethoven sonata, I only have one choice of editor/publisher if I want to play, say, any sonata by Louise Farrenc. Not having a choice of editions is a pain in the butt for a number of reasons, and I’ll go over why this is a bigger problem than mere convenience/pickiness a little further down.

The sole publishers who do offer music by women? They don’t offer everything they wrote. You’ll find their works scattered through well-meaning “select music by women” compendiums, and occasionally a single complete opus will appear with, miraculously, all the works from that opus, but comprehensive collections (e.g. all of Rachmaninoff’s preludes, or all of Prokofiev’s character pieces) as well as individual pieces (e.g. a booklet just of Chopin’s “Butterfly” etude, or Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” by itself) are virtually nonexistent.

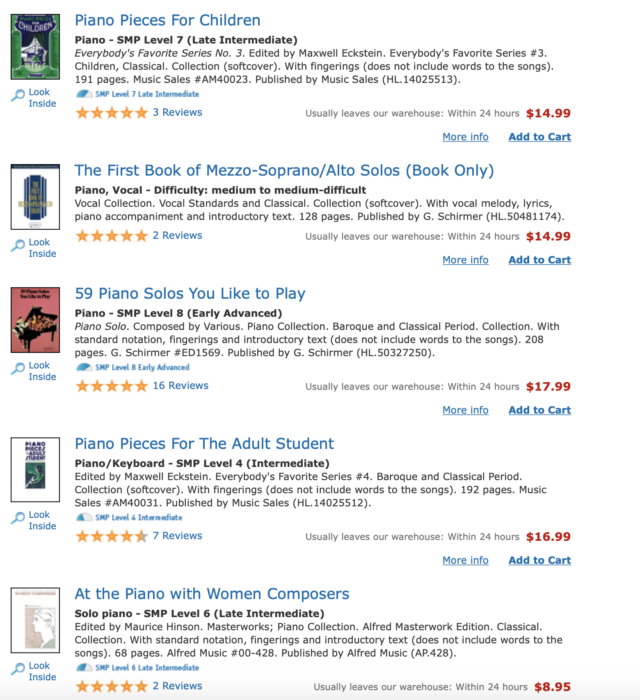

P.S. Here are the first search results on Sheet Music Plus when I do a search for “Chaminade” and filter for piano only. My homegirl Cecile, by the way, was an award-winning composer and virtuoso performing artist who wrote extensively for the piano.

2. Buying music by female composers is, across the board, a significantly more expensive proposition than buying music by standard male composers.

Because you’re locked into fewer choices (see point #1). I know this is Capitalism 101, and I fully understand that you’re paying for the lower-grossing efforts of a small group of people who put in the work to copy, edit, publish, and print music—a process that employs highly educated and specialized people who deserve to be compensated for their labor.

What I don’t like is that this places a not-insignificant financial burden on the people buying and learning said music: people who are, as far as I can tell, typically not well-known, highly-paid performers but students and independent, self-funded musicians.

- Example: if I was a student on a budget and I didn’t already have the Chopin piano etudes, I could buy a cheap edition of all 27 etudes for 10.95. (Note: I know IMSLP exists; I couldn’t live without it. But I’m keeping it out of the equation here because music teachers often loathe and sometimes forbid IMSLP printouts, the editions on it are often kind of dodgy, and largely music by non-canonic composers is nowhere to be found on there, which makes the comparison moot.)

- But if I wanted the Louise Farrenc piano etudes, I’d have to shell out $34 for the only edition available—there is no “cheapest” option, because that’s the only option. If there was a specific piece I wanted to learn that wasn’t available individually or as part of a smaller set, I’d have to buy one of the volumes of complete music; this one is $123.50, and mind you it doesn’t even tell you which pieces are in there.

I’m going to be honest: the financial aspect has affected my decision-making on which pieces to order and learn. When I was searching for music by women to play, I found some great gems cruising YouTube and the internet in general, but a lot of these more obscure pieces were in expensive (and sometimes unavailable) editions from publishers I wasn’t familiar with, and I was at the point where I’d be paying several hundred extra dollars for what amounted to a few minutes’ worth of music that might not even work out for me—it just didn’t make sense for me to take that chance.

3. The resources typically available for learning music are extremely limited once you get out of the canon.

When I’m learning new music, I usually listen to dozens of recordings for ideas, read about the writing process/reception/ideas behind the music in biographies or anthologies, and consult multiple editions of the music.

Remember how I talked about editions, and edition choices earlier? Having a multitude of editions can be extremely helpful; for example, I have four separate editions alone of the Chopin etudes (Paderewski, Henle Urtext, Wiener Urtext, and Salabert edited by Cortot) and I consult all of them when I’m learning something. Here’s how having multiple editions can be helpful:

- If I spot an error, I can check another edition to make sure it’s unintentional and to see what the correct note or marking is.

- If I’m not sure about the faithfulness of a marking or accidental, I can check to see if it appears in other editions and read the editors’ notes regarding said marking or accidental.

- If I’m unsure how much interpretive leeway I have for something, I can cross-check the different edited versions to see what’s consistent (i.e. what I shouldn’t screw with, what some different editors have suggested) and where I might have more freedom.

- Fingering.

When I’m learning a new piece of music and there’s only one published version to work with, and few recordings, I’m so much more in the dark. I can’t cross-check markings or directions, and when I find notes or markings I suspect to be errors, it causes a minor crisis—is this actually an incorrectly printed note, or is it a bold harmonic decision by the composer that I’m not supposed to mess with? If it is an error, what is the right note/marking supposed to be? I’ve had a number of instances already where I’ve found things I’m reasonably sure are errors, but have no resources to tell me what the correct notes/markings are supposed to be.

And if there’s only one recording I can access for a piece, said recording can raise more questions than it answers. Is the tempo accurate, or has the performer taken liberties for a variety of reasons? (I recently listened to a recording of the Clara Schumann piano concerto where the first movement seemed suspiciously slow, and I wondered if that was because the performer and orchestra had limited time/budget to learn and rehearse it at tempo, and if they figured that not enough people cared enough for them to get it right.) Are unmarked interpretive choices—such as an accelerando not written in the music, or crisp notes where no staccatos are marked in my edition—informed decisions based on the performer’s knowledge of the composer’s style, or are they decisions based on personal taste?

4. Your training doesn’t adequately prepare you to study non-canonic music, and mentors offer limited assistance.

I honestly feel bad saying this because I’ve been incredibly privileged to have had the type of extensive, specialized training that has resulted in me becoming a totally non-relatable person, and I have had, and continue to have, amazing mentors who have given me so, so much.

Your mileage may vary, but a lot of my training—and mind you I’ve been studying formally for 20+ years now—has been dedicated to the specifics of reading and interpreting major composers. I can tell you how a staccato in Mozart’s writing is different from a staccato in Beethoven’s early, middle, and late period writing, or how the process of determining how loudly to play a long note in Debussy’s music is totally different from what you’d do with Bach. And a lot of this knowledge comes not only from following my teachers’ instructions, but also from extensively studying music history: learning about the instruments (in some cases, how you interpret a piece by Beethoven or Chopin is influenced by what historians know about the specific instrument they wrote for), knowing how personality or events in a composer’s life shaped their writing, studying the pedagogical commandments handed down through these composers’ students, etc.

No music history course I’ve ever taken has given the life of any female composer the same attention that even “minor” male composers get. I only know slightly more than the average music major about certain female composers because of research topics I chose and reading I did on my own time.

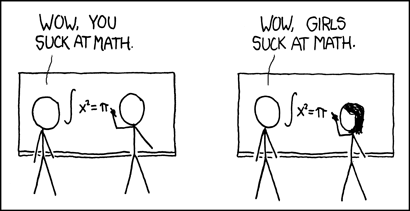

And even then when I’m learning a Chaminade concert etude or Clara Schumann’s sonata, I feel like I’m groping around in the dark. I don’t have any prior knowledge of their music or their lives to go on. I don’t know if Clara Schumann writing forte a few notes after a piano means she wants the forte to be totally sudden, Beethoven-style, or if I’m supposed to understand that there’s an implicit crescendo there. Every under-informed decision I make can end up making the music sound frigid and unmusical (a frequent criticism of art by women!), or too emotional and overly sentimental (a complete opposite but also frequent criticism of art by women!), or well-intentioned but unintellectual and poorly crafted (yet another—I think you get it).

I have been lucky to have teachers who support my self-assigned decisions and listen to music they themselves don’t know, and I have received superb musical guidance from them on interpreting and performing this music. But they don’t have definitive knowledge of Chaminade or Clara Schumann’s writing, and they’re open about the fact that, well, they don’t have the answers.

5. Interpreting less-heard music is a great way to trigger major impostor syndrome.

I’ve long come to terms with the fact that the feelings of inadequacy and fraud are totally normal side effects that come with putting your creative efforts out there. So it was rather disturbing to find that studying music by women made my impostor syndrome flare up like a grease fire, and my dudes, it was real bad.

You know everything I just said about not having enough resources or the specific training I usually have when I learn and perform standard canonic music? All of that—all the weight of those realizations and unanswered questions and search results and nights spent flipping through my books and biographies in vain—festered in my head and turned into one big, flashing LED billboard saying YOU ARE NOT QUALIFIED TO DO THIS WORK.

Usually when the impostor syndrome comes a-knockin’, I just shoo it away by saying “I am qualified! Go away!” But in this instance, it was hard to fight back because the voice of my impostor syndrome had a really good point. I know it did, because I’ve just written almost two thousand words on all the legitimate reasons I do actually feel unqualified to do this work.

“Why am I doing this? There are far more qualified people in the world who can do this better,” I found myself thinking far more than I’d like to admit. “Hell, I’m probably setting the movement back by mucking it up with my own incompetence.”

There isn’t an easy way out here. There’s always going to be someone more qualified than you at something, and all of us are going to make mistakes and fumble around when we’re striking out on new paths. But here’s the thing: it doesn’t mean the work isn’t worth doing. It doesn’t prevent you from learning something—about you, about the work—in the process. And if you don’t see a lot of other people doing work you think is important, it’s better to step forward and start doing it than to wait for some perfect savior to come along and do it for you. Be the change you wish to see, something something road less traveled, etc. etc. etc.

It’s easier said than done. My heart goes out to you out there if you, too, are doing any kind of work that makes you feel lost and unqualified.

6. There’s a very specific type of pressure that comes with working on the music of underperformed composers.

The whole point of learning this music is to eventually perform it for audiences. I’m no stranger to normal performance anxiety—like impostor syndrome, it comes with the territory and you just have to learn how to cope.

But the secretly comforting thing about playing music that everyone already knows is that well-known music is pretty forgiving. Don’t get me wrong, performing is terrifying no matter what you’re playing, but through very unscientific study, I’ve noticed that (non-academic) audiences tend to fill in the imperfections when you play music they know. Your less-than-stellar rendition of a beloved composer is also unlikely to ruin their love of that composer—I’ve never heard of anyone leaving a concert going “Well that performance of Gretchen am Spinnrade has ruined all of Schubert’s music for me!”

But I’m preparing the music I’ve selected fully knowing that for the vast majority of my audience members, this is going to be their first ever exposure to these composers. They are going to make value judgments (“This composer is good and I like their music”) on a composer’s entire oeuvre based on this one singular impression. If I flub some harmonies or get too pokey with my staccatos or fail to adapt to a venue’s piano in real time and get thick in my chord voicing, an audience member who has never heard anything by Clara Schumann is probably not going to think “The piece is great but the pianist needs to refine her ideas”—they’re more likely to say to themselves, “Well, I suppose this is why people should only play Robert Schumann’s music.”

And damn, that’s a lot of pressure.

The art of performing is an art fraught with anxiety, and that anxiety is compounded when you feel like you alone bear the weighty responsibility of validating the existence and toil of an artist who can no longer speak for themselves. It seems unfair that the countless sloppy performances of Chopin’s music can’t remotely hurt his worldwide appeal, while one off performance of Florence Price’s sonata might leave a local audience politely clapping while privately thinking that that’s the last time they’ll humor an artist trying to expand their horizons. That fear feeds right back into the impostor syndrome, that feeling that maybe someone better, more talented, more famous, more charismatic than you should be spearing this particular charge.

I’m not saying this for the sake of complaining, or because I want pity points—I’m writing about these challenges because I know I’m not the only person doing off-the-beaten-path work, and if the internet has taught me anything, it’s that other people out there are feeling the same things I’m feeling. And if you’re about to embark on a new project that involves wandering into uncharted territory, you’re going to experience these challenges.

But there are so many upsides to doing this work! I’ll get into all the happy, shiny things I’ve learned so far in Part 2.

If you liked this post and would like to see more writing like this, please consider supporting me on Patreon. By doing so, you’ll enable more blog posts, as well as future projects like recording the music I’m writing about!

Leave a Reply